The following information provides an overview of the issue of women in society. The focus is specifically on women in America and even more specifically on women in higher education.

The Role of Women in Society

It goes without saying that gender roles have evolved over time, although how much and in what ways varies considerably, depending on culture. It is the goal, by definition, of any egalitarian society to achieve gender equality and the general movement worldwide has been in this direction, with greater success in some societies than in others. Even though we in America tend to think of ourselves as advanced in any number of global attributes, gender equality is perhaps one area in which that assertion is inaccurate, as the following video illustrates. This is a 2013 PBS video on gender equality in America that looks at the methods used to achieve greater gender equality in other countries and touches on the general health of Americans as well.

Feminist Issues

Former President Jimmy Carter has stated that he is devoting the rest of his life to the welfare of women and addressing inequities in how women are treated, calling it the most important unaddressed problem in the world. He has published a new book and devoted the Carter Center to this issue, featured on a webpage called the Forum on Women’s Issues. The video below is a discussion of his book and an international forum, “Beyond Violence”, that he hosted in February of 2015. The video gives a good general overview of feminist issues in the modern world, including gender inequality issues in America.

It should be noted that both of the previous videos, the PBS report and the interview with President Carter, reported US ranking using 2013 data. The latest data from the World Economic Forum shows that the United States has moved from 23rd place to 20th (2014).

Continuing Barriers

What are the specific barriers present in America that tend to limit gender equality, or at least demonstrate this inequity? The following are barriers that illustrate the issue with emphasis on measurable findings.

Violence Against Women

Violence against women is obviously an issue of worldwide significance. In the context of higher education, violence against women is primarily embodied in sexual assault on campus. In 2014 President Obama attempted to draw national attention to this problem, meeting with his Council on Women and Girls, who later released a report on actions taken (Calmes, 2014). According to this article, one in five college students report being raped while in college, although only 12% report the assault and assailants are rarely charged or convicted.

Part of the difficulty in addressing the problem of sexual assault on campus lies in reporting issues, from lack of consistency in the definitions used to allegations of intentional underreporting on the part of university officials. The Clery Act, signed into law in 1990, requires higher education institutions to report a variety of crimes, including violent and non-violent sex offenses. The Department of Education (DOE) performs periodic in-person audits of the crime statistics and reporting practices of universities. These statistics and audits form the basis for a study in which reports of campus sexual assaults prior, during, and post DOE audit were used to empirically assess reporting issues (Yung, 2014).

Part of the reason for this study lies in the huge disparity in rates of sexual assault. As mentioned above, the Campus Assault Study (2007) found that 20% of women on large university campuses reported being raped while there and yet the Clery Report statistics indicate a rate of only 0.02% of students raped in a given year (Yung, 2014). Yung found that, even after accounting for 5-year college enrollment and underreporting by victims, Clery reporting seriously lagged behind rates found in other studies. Additionally, and interestingly, it was found that rates of rape reported by universities spiked during DOE audit periods, returning to pre-audit rates the next year (Yung, 2015). The sexual assault rates are, in fact, 44% higher during DOE audit periods while reporting rates for other crimes on campus do not show a similar spike (Yung, 2015). Although other possible explanations for the spike were considered, the findings are consistent with the hypothesis that is it the ordinary practice of universities to under report sexual assault (Yung, 2015). Possible explanations of such behavior, consistent with other studies on societal and law enforcement behaviors and beliefs, include widespread adoption of ‘rape myths’ and exaggerated belief in false reporting by women (Yung, 2015). Professional incentives to under report are also possible.

Efforts are underway from a variety of sources to combat the problem of campus sexual assault and raise awareness of the issue as well as provide specific suggestions for intervention. For example, the University of Kentucky (UK) has developed and is actively promoting the Green Dot Program, which focuses on preventing perpetrator behavior by providing students with skills to be proactive bystanders (Bessette, 2015). Developed by Dr. Dorothy Edwards, who was motivated by watching past campaigns fail to make a difference, the training is required of all incoming freshmen at UK. Her work is grounded in social diffusion theory, bystander literature, perpetrator data, and marketing research and has been shown to be effective in a study of nearly 8000 college students; those who had the training had significantly lower rape myth acceptance scores and reported engaging in significantly more bystander behaviors than those who did not receive training (Coker, Cook-Craig, Williams, Fisher, Clear, Garcia & Hegge, 2011).

The following four minute video was published in 2014 by the College of Charleston, although not in conjunction with UK or its Green Dot Program. The video illustrates the potential impact of bystander behavior.

Women in Positions of Authority

This section reviews the preparation of women for positions of authority and prestige, along with information about the actual attainment of those positions, in political, business, and higher education environments.

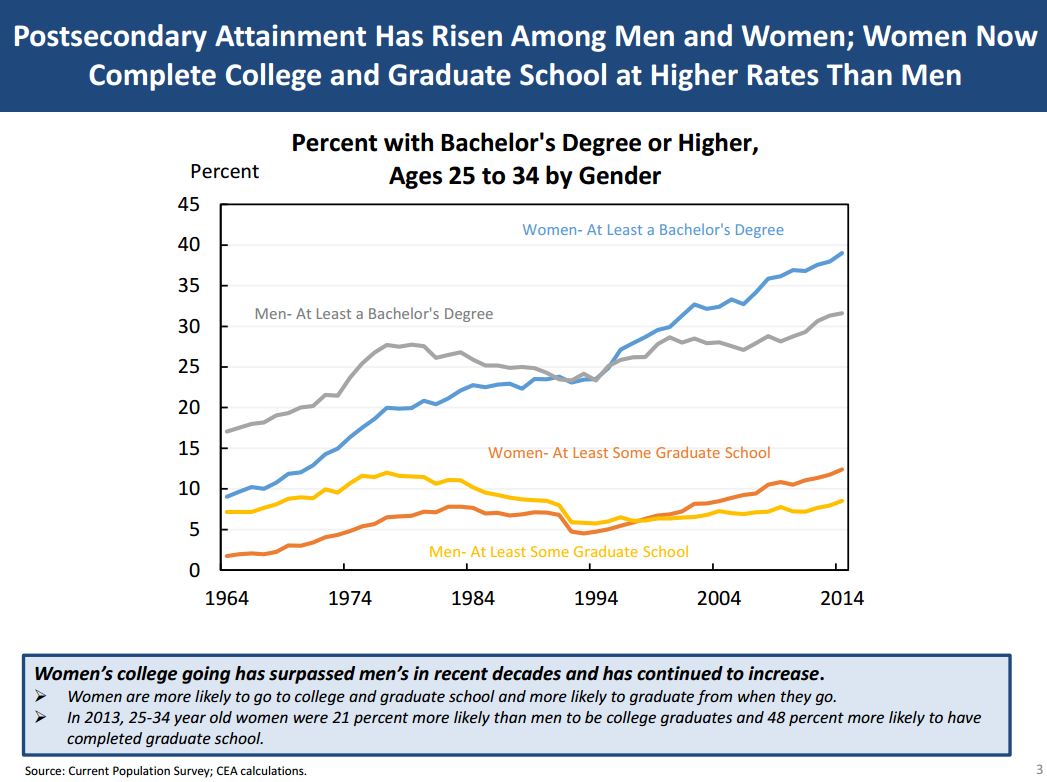

For a number of years now female enrollment in higher education has exceeded male enrollment among caucasians. It appears that females of other ethnicities are also now exceeding male enrollment, according to a study by the Pew Research Center (2014). In 1994, 61% of caucasian male high school graduates enrolled in college the following fall while 66% of females did so; by 2012 the percent of caucasian males enrolling in college remained unchanged while the percent of caucasian women enrolling increased to 71% (Pew Research Center, 2014). In that same time period, among hispanics, blacks and asians in America, while male high school graduates equaled or out paced females going on to college in 1994, by 2012 the number of women going on to college exceeded the number of men in all three groups (Pew Research Center, 2014). Women also graduate from college and attend graduate school in higher numbers than men.

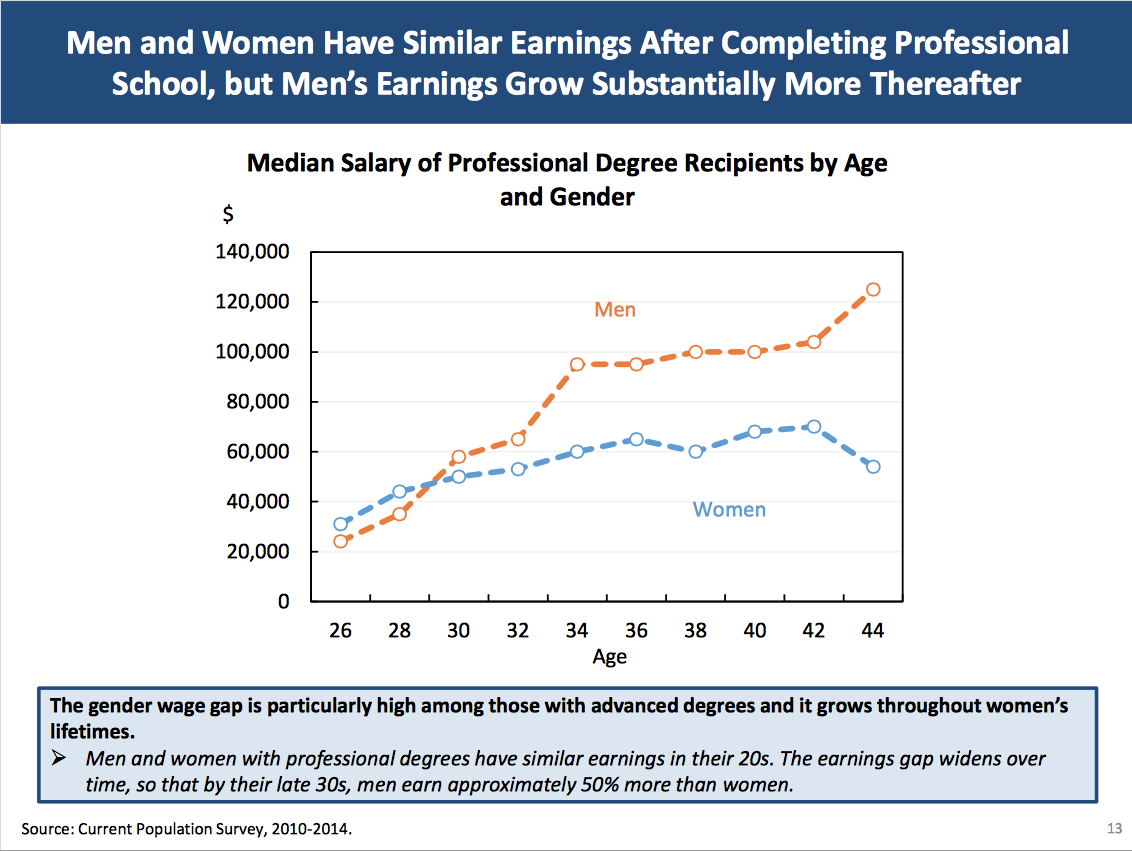

Despite these educational achievements, women continue to hold fewer positions of authority and are paid less than men when they do. Women who are employed full-time and year-round earn 78 cents for every dollar earned by a man in America (Council of Economic Advisors, 2014). This gap widens with increased professional achievement (see below).

As our 114th Congress starts it is with the participation of a record number of women – 104 Senators and Representatives, representing 19% of Congress (Pew Research Center, 2015). To put this in perspective, in 2008 the US, with 16% of the Senate and 16.8% of the House held by women, ranked 68th of 134 nations in national representation by women while the Nordic countries (who held the top positions) averaged over 41% for the number of female representatives in their parliaments (IWDC, 2008).

In Fortune 500 Companies women hold 5% of the CEO positions and 17% of the positions on the boards of those same companies (Pew Research Center, 2015). This represents the 8th year in a row of no significant change in the number of women on boards while 135 of the Fortune 500 companies have zero women in executive positions and many continue with all male boards (Catalyst, 2013).

When it comes to institutions of higher learning the differences continue to be notable. As mentioned previously, women graduate from colleges and graduate schools in higher numbers than men with recent statistics showing that 57% of all college enrollments are women and 59% of all degrees are conferred on women (University of Denver, 2013). Women also outpace men in national research grants and awards, with 56% going to women and 44% to men (University of Denver, 2013). These achievements do not translate into status, salary, or leadership positions, however. Women in academia are over represented among instructor and lecturer positions and under represented in tenured doctoral positions, where they earn on average 20% less than male faculty (University of Denver, 2013). It is noted that this is the opposite of the trend seen in other sectors where among public employees the gender pay gap is less than in the private sector.

Is progress being made to reverse this trend, and from what areas can such progress be expected to come? A recent poll of Americans found that the majority see women as just as capable as men in both the boardroom and in congress; they also see women as just as intelligent and innovative as men and with greater compassion and organization (Pew Research Center, 2015). When asked why they think women are not achieving the top level in leadership positions, the top two responses were that women are held to a higher standard than men and that companies are not yet ready to put women in those positions (Pew Research Center, 2015). A majority of Americans also believe that this is not likely to change and that men will retain control of most top business positions, while 73% expect to see a female president in their lifetime (Pew Research Center, 2015). Perhaps not surprisingly, while over 65% of women believe that gender discrimination still exists in America, less than half of men do (Pew Research Center, 2015). It is the conclusion of the University of Denver study (2013) that women outperform men but do not receive the salary or title this should garner and that the evidence is that the reason for this is a bias against women in leadership positions.

Is progress being made to reverse this trend, and from what areas can such progress be expected to come? A recent poll of Americans found that the majority see women as just as capable as men in both the boardroom and in congress; they also see women as just as intelligent and innovative as men and with greater compassion and organization (Pew Research Center, 2015). When asked why they think women are not achieving the top level in leadership positions, the top two responses were that women are held to a higher standard than men and that companies are not yet ready to put women in those positions (Pew Research Center, 2015). A majority of Americans also believe that this is not likely to change and that men will retain control of most top business positions, while 73% expect to see a female president in their lifetime (Pew Research Center, 2015). Perhaps not surprisingly, while over 65% of women believe that gender discrimination still exists in America, less than half of men do (Pew Research Center, 2015). It is the conclusion of the University of Denver study (2013) that women outperform men but do not receive the salary or title this should garner and that the evidence is that the reason for this is a bias against women in leadership positions.

Given the belief by the majority of men that gender bias does not exist, and the continued dominance of men in position to elect or appoint leaders, this situation does not seem likely to change in the near future in America, certainly not in those industries or institutions where exclusive or near-exclusive male leadership currently exists.

_________________________________________________________________

References

Bessette, L.S. (2015). How U Kentucky is trying to stop campus sexual assault. Women in Higher Education, 24(1), 6-7. Retrieved from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/whe.20152/asset/whe20152.pdf?v=1&t=i84jeqpa&s=0fceea2ac089517de33cd573a1ef7dd0f25494a6

Calmes, J. (2014). Obama seeks to raise awareness of rape on campus. The New York Times, A18. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/23/us/politics/obama-to-create-task-force-on-campus-sexual-assaults.html?_r=0

Carter, J. (2014). A call to action: Women, religion, violence, and power. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Catalyst. (2013). Census of Fortune 500: Still No Progress After Years of No Progress. Retrieved from: http://www.catalyst.org/media/catalyst-2013-census-fortune-500-still-no-progress-after-years-no-progress

Coker, A.L., Cook-Craig, P.G., Williams, C.M., Fisher, B.S., Clear, E.R., Garcia, L.S. & Hegge, L.M. (2011). Evaluation of Green Dot: An active bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence on college campuses. Violence Against Women, 17(6), 777-796. Retrieved from: http://vaw.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/06/02/1077801211410264

Council of Economic Advisors. (2014). Women’s participation in education and the workforce. Retrieved from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.documentcloud.org/documents/1350163/women_education_workforce.pdf

International Women’s Democracy Center (IWDC). (2008). Women’s political participation: Women in parliaments. Retrieved from: http://www.iwdc.org/resources/fact_sheet.htm

Krebs, C.P., Lindquist, C.H., Warner, T.D., Fisher, B.S. & Martin, S.L. (2007). The campus sexual assault (CSA) study. Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/221153.pdf

Pasque, P.A. & Nicholson, S.E. (Eds.). (2011). Empowering women in higher education and student affairs: Theory, research, narratives, and practice from feminist perspectives. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Pew Research Center. (2015). Women and leadership: Public says women are equally qualified, but barriers persist. Retrieved from: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/01/14/women-and-leadership/

Pew Research Center. (2014). Women’s college enrollment gains leave men behind. Retrieved from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/03/06/womens-college-enrollment-gains-leave-men-behind/

University of Denver. (2013). Benchmarking women’s leadership in the United States. Retrieved from: http://www.womenscollege.du.edu/media/documents/BenchmarkingWomensLeadershipintheUS.pdf

World Economic Forum. (2014). The Global Gender Gap Report 2014. Retrieved from: http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2014/rankings/

Yung, C.R. (2015). Concealing campus sexual assault: An empirical examination. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 21(1), 1-9. Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/law-0000037.pdf